Steven Rubin’s Marcellus Photos at the Gmeiner

January 3, 2016

Photographer Steven Rubin graciously provided eight brilliant photos for Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone. You can see more of his photos in an exhibit called “Fractured State” at the Gmeiner Art and Cultural Center in Wellsboro starting today. His photos will be showing until January 31, when we will be co-hosting a closing reception. Here’s more.

Steven Rubin and Anna Rogers hanging photos.

Early Praise for Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone

July 30, 2015

by Jimmy

PtSZ went to the printer this past Friday. Here’s what readers are saying:

“Pedaling through some of the country’s loveliest–and hardest-used–countryside, the author provides the rare combination of information and wisdom. This is a real act of witness.” — Bill McKibben, author of Deep Economy

“Navigating terrain, cresting hills, glimpsing wildlife at one turn and drilling rigs at another, Jimmy Guignard literally and figuratively cycles the reader through the fraught landscape of his family’s life in the ‘sacrifice zone.’ This is an essential and approachable book for understanding the impact of the natural gas industry on a place as well as on a people. Emphasizing the power of rhetoric as a tool for understanding the industry, Guignard offers an honest and searching account of what it means to live consciously, energetically, and passionately in a place wracked by technological change, uncertainty, and corporate power dynamics.” —Eileen E. Schell, coauthor of Rural Literacies (Studies in Writing and Rhetoric) and coeditor of Reclaiming the Rural: Essays on Literacy, Rhetoric, and Pedagogy

“In Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone, Jimmy Guignard leads us on a nuanced journey through the hard truths and complex narrative frames of Marcellus shale production in rural northeastern America. “Contact! Contact!” Henry Thoreau advised us about our relationship to landscapes. Guignard pedals right up close to the solid earth, the actual world, and where he lives it now sadly smells more and more like cheap gas and high corporate profits.”—John Lane, author of Circling Home

“Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone reads like a mystery novel, replete with fully fleshed out characters who may or may not be guilty of crimes against humanity, a compelling dramatic time line, a hard-boiled, beer-drinking, bike-riding environmental detective, and richly drawn sense of place. So engrossing is the story Guignard tells we almost don’t notice how much we’re learning about fracking, environmental rhetoric, and the coming of age—no, the maturing—of a man who cares deeply about the physical world and what we are doing to it. A lovely mix of scholarship and personal narrative, this book should be required reading for anyone interested in nature writing and the frustrating world of fracking.” —Sheryl St. Germain, author of Navigating Disaster: Sixteen Essays of Love and a Poem of Despair and Swamp Songs: The Making of an Unruly Woman

I’m pretty stoked, to say the least. You can pre-order your copy from your favorite local bookstore anytime. Thanks and more soon!

Pre-Order Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone

July 14, 2015

by Jimmy

Back in town after a long trip out west with Lilace and the kids (which was awesome). I have been trying to catch up on work and other stuff when I saw that Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone has appeared at the TAMU Press website. You can check it out here. You can also pre-order on Amazon or from your local bookseller. My go to place for books: From My Shelf Books & Gifts in Wellsboro, PA.

On the way back, we drove through the “Energy Capitol of the Nation”: Gillette, Wyoming. I’m scribbling a blog post about that. I have another post cooking up about my ASLE presentation and a few in the works from guest bloggers. More soon!

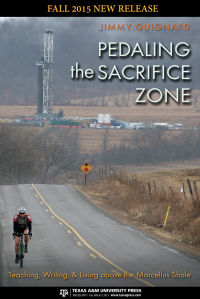

Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone Book Cover (Whoohoo!)

May 28, 2015

by Jimmy

I haven’t been here in a while, but I’ve got a list of stuff to cover as I get back into the swing of the bloggins. But I thought I’d share the cover my forthcoming book, Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone, which has been turned into a poster for a promotional gig* later this summer. Lilace Mellin Guignard shot the photo (thanks, Honey!) and Texas A&M University Press did the rest.

Pretty sweet!

Now, I’m waiting on the proofs, logging some bike miles (saw two osprey Sunday), and plinking away at department chair stuff. I’ll be posting more frequently. Keep an eye out, if you’re of a mind. As always, thanks for reading.

*I will be attending an author’s reception at the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment Conference this summer at the University of Idaho in June. In addition, Lilace and I are presenting with Ann Green of Saint Joseph’s University and Ted Fristrom of Drexel University about what it’s like to teach writing and energy literacy above the Marcellus shale.

The Redneck Pastoral (Part 2)

November 15, 2014

by Jimmy

NOTE: This is part 2 of an essay called “The Redneck Pastoral” I read at the English Association for Pennsylvania State Universities Conference at California University of Pennsylvania this past October. This excerpt comes from chapter 6 of my book manuscript called Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone: Teaching, Writing, and Living above the Marcellus Shale.

“You ready to go back to the fire, Gabriel?” Eric asked.

“Yeah,” Gabe said. Eric fired up the Ranger, put it in gear, and pressed the accelerator. The engine whined, the tires spun, kicking up snow and ice, and the Ranger moved forward about an inch. Eric slammed it in reverse and tried to back up. Same result. He tried to go forward and backward a few more times. We moved maybe two inches. He stopped and put the engine in neutral. “Well, goddamn it, I think we’re stuck.”

“Let me push,” I said. “Gabe, you stay here. Hold on tight.” I jumped out, waded through two feet of snow to the rear, told Eric to “hit it,” and pushed for all I was worth. Snow and ice bounced off my chest and legs. The Ranger revved, tires spinning. Didn’t budge.

“Eric!” I yelled, competing with the revving engine. He let up on the accelerator. “Let me jump in the bed and rock it while you floor it.” I climbed in the bed, grabbed the roll bar, braced my feet against the sides, and said, “Go!” Eric floored the Ranger again while I yarded from side to side on the roll bar. The Ranger rocked as snow and ice slapped against the sides and underbody. No luck. “Stop, man!” I yelled. “We’re stuck good.” I started laughing. Gabe sat silently in the front seat, hands wrapped around the bar on the dash. Eric stared down at the steering wheel for a moment, shut off the engine, then hopped out of the cab and started clearing snow from under the Ranger with his arms. I jumped out of the bed to help. Gabe hopped out and watched. I said, “Whaddya think, buddy?” He shrugged. Once again, we heard the drill rig’s implacable grinding and roaring.

After a few minutes of digging, we saw we were hosed in two ways. First, Eric had stopped the Ranger in a swale, which meant the snow was deeper here than in the rest of the field and that the snow sat on ice which had frozen in the bottom. The Ranger cut its way down into the ice just like a drill bit cutting into the earth, settling the underbody on packed snow. We were stuck good. I laughed again when I saw the chained tires sunk four inches or so into the ice. It looked like we had four flats. Eric said, “Reckon we should go get Rick’s tractor.” I volunteered to walk with Gabe back to the fire pit and tell Rick. Eric said he’d stay with the Ranger. He grabbed a beer from Rick’s cooler, opened it, took a swallow, set it down in the cab, and commenced to digging again. When Gabe and I looked back from the top of the field, we could see his crouched figure, snow flying, like a dog digging after a groundhog.

As we walked into the woods, I heard the poppoppop of Rick’s tractor headed our way. Since we’d been gone so long, Rick figured that we were stuck. He drove out of the woods toward us, stopped, and idled down the engine. I told him where Eric was, and Gabe and I slogged on to the fire pit. A few minutes later, we walked up on Tom, Sheila, and Francis standing around the fire and filled them in on the night’s shenanigans so far. Gabe grabbed a root beer and a bag of chips. I stood at the fire for a few minutes, until Francis and I decided to walk back down to see if we could help. I made sure Gabe was warm and well supplied with kid beer and food, and that Sheila and Tom would stay with him until I got back. Francis and I set off for what became a comedy of errors.

We were slipping down the hill toward the finger of forest separating the fields and lamenting the booze we weren’t consuming when I noticed three separate sets of lights below us: the Ranger, the tractor, and the drill rig. “Oh, shit,” I said, “Rick got the tractor stuck.” Sure enough, when we walked through the woods to the ditch that bordered the field above the Ranger, Rick stood beside his tractor, cursing. I saw that the rear blade he used for moving snow had caught one side of the ditch as he drove through it, stranding the rear tires an inch or two off the ground. He couldn’t raise the blade any further and the tires couldn’t get traction. He was stuck good. I laughed, and turned to Francis, “This is turning hilarious.”

Things moved from hilarious to absurd. We tried to push the tractor out. Dumb. Eventually, we freed the tractor when Rick detached the blade by pounding the pins out with an anchor shackle. Rick drove down to the Ranger, pulled it out, and got the tractor stuck again. Eric buried the Ranger in another swale trying to get back to the tractor. We dug snow from around it and pushed it out. Then Eric pulled the tractor out. Both pieces of equipment freed, Francis and I jumped on the Ranger, Eric high-tailed it out to Ikes Road, and motored back to the fire pit via dirt roads, arriving about 3 a.m. I must have burned more calories digging in and walking through the snow than I do on a fifty-mile bike ride. Since I hadn’t tasted any beer or bourbon in several hours, I told Gabe we’d be heading home soon. Around the fire, we recounted our heroic deeds to watch $100 bills shooting out of the ground one more time, laughing at the absurdity of it. Gabe and I left the fire around 4:00 a.m.

I thought Gabe might go to sleep on the way home, but he told stories from the fire all the way, each punctuated by his belly laugh. We crept into the house, trying not to wake anyone up. I hustled him off to bed and fell into bed myself, smelling of smoke and thinking that was ridiculous. The Redneck Pastoral. Awesome.

I woke up thinking about coffee and the rig towering above our shenanigans in the field. How the rig represented something huge, an energy and technology revolution, while we, a small group of partiers wallowing in the snow at its base represented what . . . the community? The place? We were apart from the industry, yet also somehow a part of it. In the light of day, the well pad seemed simultaneously too close and too far away, a single rig and a symbol for a vast system. The rig drew us to it with the promise of seeing $100 bills shooting out of the ground, even though it stood impersonal and impenetrable while we tried to free our machines. If it hadn’t been there, we would have stayed around the fire, I would have drunk more bourbon, and Gabe and I would have slept in the Man Hut. The rig gave me a sense that we were being watched, even though we were on private property and doing nothing wrong. We were stuck in the industry the same way we were stuck in the snow, but we couldn’t dig ourselves out. We were having our fun, celebrating a memorable birthday, but that rig left its stamp on the proceedings.

I ground coffee beans and thought about those lovers in Ridley Scott’s Titanic. Our adventure in the field reminded me of the unlikely affair Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet’s characters’ have in the midst of a massive tragedy-in-waiting. They were living their lives when the ship hit the iceberg. At Eric’s party, we were living our lives in the midst of a huge drama playing itself out around us over hundreds of square miles. Perhaps, depending on which way the drill bit pointed, even right below us. We could have been wrestling with stuck machines directly above a drill bore. Or the drill bit could have been chewing its way along under the fire pit. Scott’s lovers’ story takes place against the historical backdrop of a disaster and, while the lovers and the movie goers see their story as central, it’s dwarfed by the larger story of the hubris that sank the ship. Thinking back over the previous night, I saw my life as very small compared to the industry. Thankfully, we wouldn’t hit an actual iceberg, but who knew when something irreversible might happen, like a polluted water well. That night’s craziness a short walk from the well pad drew in stark relief the extent to which my family and I were acting in our daily dramas while the industry chugged around us and beneath us, carrying us into an uncertain future. That’s part of the problem with the industry. We know where they are, but we don’t know where they are going.

The Redneck Pastoral (Part 1)

November 15, 2014

by Jimmy

NOTE: Back in October, I presented an excerpt from Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone: Teaching, Writing, and Living above the Marcellus Shale at the English Association of Pennsylvania State Universities Conference at California University of Pennsylvania. Now, I’m working to get a copyedit-ready manuscript to Texas A&M Press by December 1. The book is scheduled to appear in fall 2015. Anyway, thought I’d share the excerpt in two parts. This is part one.

About 6 p.m. on January 29, 2011, Gabe and I loaded the Corolla with chips, root beer, a case of Yuengling, a fifth of Maker’s Mark, and warm clothes and headed through a snow storm to the Old Man’s house. It was his sixtieth birthday.

Snow fell thick as I backed out of the garage and steered down the driveway. Fifteen minutes later, we spun up the Old Man’s driveway past the sign that states “Hey, asshole, this ain’t your fucking land. Go away now or you’ll be mistaken for a large, annoying squirrel,” and parked beside his truck.

Gabe and I grabbed our supplies out of the car and slogged through eighteen degree temps and eighteen inches of snow past Eric’s Man Hut to the old logging road that led a quarter mile down toward the sugar shack. We slipped through the woods toward the flicker of the fire on the trees until we heard Eric pontificating about some adventure from his past. We rounded the corner of the sugar shack to Eric’s “Well, look here! Hey, Gabriel! How you doing?”

“Good,” Gabe said. “Happy birthday.”

I put down the Yuengling and showed Gabe where he could put his chips and kid beers in the sugar shack, a ten by ten unfinished room with a big overhang on one side. A couple of old restaurant chairs and scattered newspapers made up the décor. As we headed back outside, I said, “If you get cold, you can come in here, OK?” He nodded, root beer in hand, and led me past the stainless steel vats back to the fire about twenty feet away. Split ash burned brightly in the brick fire pit. On the open side of the pit, three logs stood on end, serving as seats. Split firewood was stacked all around us, some on pallets, some stacked in rows taller than my six foot, three inch frame. Eric, Tom, Sheila, Francis, and Rick, Eric’s neighbor, had stomped the snow down around the fire. Gabe took a seat on a log. I wondered how long he would last in the snow and cold.

Since I hadn’t seen Rick in a few months, I walked over and stuck out my hand. “How ya doin’?”

“Good, good,” he replied. Rick’s a huge guy with a big beard who carries a cooler of Milwaukee’s Best in his Polaris Ranger and a .357 in his back pocket. We chatted a minute before I spied a case of Arrogant Bastard stuck in the snow on the other side of the fire, the Maker’s Mark buried beside it. I picked up the Yuengling and carried it to the pile. Setting it down, I opened the case, pulled out a beer, and asked if anyone needed one. Hearing no takers, I opened the beer, shoved it down in the snow on top of some firewood, and grabbed the bourbon. I opened the bottle, said “Here’s to the Old Man!” and took a pull.

“The Old Man!” the others exclaimed. I passed the bottle to Eric, who took a swallow and passed it around. The bottle circled the fire, only Gabe and Sheila abstaining. When Francis passed it back to me, I capped the bottle and shoved it back into the snow. Then we settled into some beer drinking and bullshitting about bikes and bike races as the temperature and the snow continued to fall.

As we stood around the fire recounting tales of epic rides and giving each other shit, gas workers drilled the Vandergrift 290 5H well about 1500’ away as the crow flies. I knew they were drilling because I had ridden my bike past the well on Ikes Road several times. And Eric kept me updated. This night, the well pad seemed miles away in the dark and cold and the flurry of words around the fire. Almost another world. One flurry: Eric told us how he always goes to Rochester on his birthday and test drives a $180,000 RV just to, as he called it, “tease the salesman.” The conversation drifted away from the RV test drive story like smoke from the fire, then circled back when Eric said, “I love teasing those guys on my birthday. You’ve gotta try it sometime. I love fucking with them.”

The fire burned low. Eric said, “I hope we can find some wood.” The line became one refrain to our circuitous conversation about bike rides, making maple syrup, drinking moonshine, and growing up in Tioga County. Francis piled more wood on the fire. The ash caught quickly and pushed the cold back a little. Finally, the drill rig made an appearance when Rick turned to Gabriel. “Gabe,” he asked, “you want to ride over and see $100 bills shooting out of the ground?” Gabe looked at me. Rick’s 4×4 Ranger sat behind us, the fire glinting off the dull green paint and plexiglass windshield partially covering the cockpit. No doors. Cooler in the bed. Knowing he wanted to ride the Ranger in the snow, not see the gas well, I said, “You want to?” Gabe nodded.

“Let’s go then.” We set down our beers and walked to the Ranger. Rick fired it up and drove us through swirling snow along an old logging road to a field where corn grew in summer. We skirted the field, catching a glimpse of the drill rig lights through the trees, before Rick turned down hill, wove through some trees, dropped through a ditch, and crawled across another field through deep, super-fine snow. Ablaze in lights, the blue and white rig stood about two hundred yards away. Rick stopped the Ranger and killed the engine. The roar of powerful engines filtered through the air toward us. “See, Gabe?” Rick asked. “Hundred dollar bills shooting out of the ground.”

Jutting ninety feet into the air, the rig was impressive. Tank trailers, generators, compressors, and trucks clustered around the rig. An American flag whipped and popped from the pole on top. A grinding roar permeated the night, dulled somewhat by the snow falling and blanketing the ground. As I looked at the rig, Dickens’ Coketown popped into my head. I looked closely for Stephen Blackpool walking the pad, but I couldn’t see him. Rick no doubt saw money “shooting out of the ground.” Who knows what Gabe saw? We sat there another minute looking at the rig, snow swirling between the rig and the Ranger, listening to the bit chew into the earth. I wondered whether the guys working the rig saw us. Rick asked Gabe if he was ready to go back to the fire. “Yeah,” Gabe replied, and off we went, spinning back up the hill to a fire pit that struck me as a scaled-down version of a well pad where we engaged in that age-old ritual of gathering around a source of burning energy, conversing and trying to stay warm.

Eric, Gabe, and I jumped back in the Ranger about 12:30 a.m. Eric eased out of the fire pit’s light, the Ranger’s headlights lighting the tracks from previous forays. He puttered along the tracks, eased across the field into the woods, and dropped down through the drainage ditch into the faint glare of the drill rig, his instincts and experience handling equipment overpowering the booze flowing in his veins. He said, “Look at those $100 bills shooting out of the ground, Gabriel!” Then, as the field flattened, he floored it.

The Ranger bucked and fishtailed through the snow. Gabe laughed at first, until the snow sprayed between the windshield and the hood, hitting him in the face. In protest, he pulled his knit hat down over his face. I laughed and yelled over the engine, “What’s the matter, buddy?” Eric glanced down to see Gabe’s cap pulled down over his face and slowed the Ranger to a stop near where Rick, Gabe, and I had stopped before. “Did that bother you, Gabe?”

“Going fast doesn’t,” Gabe said. “The snow hitting my face does.”

“Ok,” Eric said. “We’ll stop.” He pointed at the rig. “Look at those $100 bills shooting out of the ground.”

We sat there for a minute, and I wondered how Eric felt about the rig, considering some of those bills ended up in his bank account. My guess from conversations we’d had around fire rings and on bike rides was that he was torn. His father had leased his property before he gave the property to his kids, so in some ways Eric had no choice. Eric has a soft spot for nature, and he worries about climate change. He’d watched the gas workers closely when they crossed his property and fought with them to re-route pipeline around a small wetland. He appreciated the lease money and I guessed from the references to $100 bills shooting out of the ground, he looked forward to the royalties. But he also knew that he had lost something in return for the windfall, perhaps mostly peace of mind. I sensed a twinge of bitterness each time he talked about the industry, and I sometimes saw outright rage.

This night, Eric seemed giddy at the promise of the money from the drilling, maybe the only time I’ve seen him in that state of mind, and I didn’t blame him. He’d served in Vietnam, worked his entire life in construction and the trucking industry, and since losing his driving job, he worked seasonally for the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Physically, he’s beat up, though he can tolerate more pain than anyone I know.

If anybody deserved a natural gas windfall to ease stress, it was Eric. Yet the promise of gas industry money did not always seem to outweigh the costs. But on this night, nobody gave a shit. We just watched $100 bills shoot out of the ground and repeated stories we had all heard before, and loved.

See next post for part 2.

My (Partial) Natural Gas Reading List (Updated)

August 31, 2014

by Jimmy

I haven’t been here in a while, because I was in the throes of finishing my book for Texas A&M University Press called, tentatively, Pedaling the Sacrifice Zone: Teaching, Writing, and Living above the Marcellus Shale. The manuscript was due July 1, and I’m happy to say I met the deadline.

Because my book is largely about how words and images shape perceptions of the Marcellus, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about books (and other texts) that shaped my own views of living in the frack zone. I won’t have room to include these titles in the book itself, so I thought I’d share them with you. I’ve attempted to break them up into categories (nebulous at best), and each of these books (including some films) shaped my thinking in some way over the past four years. (Note: This list does not include the blogs and academic articles I read.)

Nonfiction

- Rick Bass, Oil Notes (Bass was a geologist searching for oil before he became an environmentalist and activist. After reading this book, I understood the attraction of drilling for fossil fuels. A bonus: the guy can write.)

- Robert Bryce, Gusher of Lies: The Dangerous Delusions of “Energy Independence”

- Walter M. Brasch, Fracking Pennsylvania: Flirting with Disaster (Tons of research in this book.)

- Alexandra Fuller, The Legend of Colton H. Bryant (Absolutely awesome writing. Read this book.)

- David Gessner, The Tarball Chronicles: A Journey Beyond the Oiled Pelican and Into the Heart of the Gulf Oil Spill (This book played a tremendous role in my thinking about my book.)

- Russell Gold, The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World (

I’m reading this one. Slowly.Done. Great book.) - Daniel Goleman, Ecological Intelligence: The Hidden Impacts of What We Buy

- Stephanie C. Hamel, Gas Drilling and the Fracking of a Marriage (Raises some interesting tensions about a married couple with differing views on leasing.)

- Richard Heinberg, Snake Oil: How Fracking’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future

- James Howard Kunstler, The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century

- Lisa Margonelli, Oil on the Brain: Adventures from the Pump to the Pipeline

- Seamus McGraw, The End of Country

- Bill McKibben, Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet

- Bill McKibben, Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist

- Bill Powers, Cold, Hungry, and in the Dark (Focuses on past production rates and markets.)

- Vikram Rao, Shale Gas: The Promise and the Peril

- Sandra Steingraber, Raising Elijah: Protecting Our Children in an Age of Environmental Crisis (Includes a chapter on fracking.)

- Tom Wilbur, Under the Surface: Fracking, Fortunes, and the Fate of the Marcellus Shale (Wilbur has a good website, too.)

- Gregory Zuckerman, The Frackers: The Outrageous Inside Story of the New Billionaire Wildcatters (Interesting read, though I’d be put in jail if I pulled some of the crap these guys did.)

Fiction

- Lamar Herrin, Fractures (A bit didactic, though it captures nicely the tensions created among people when gas leasing is involved.)

- Nick Hayes, The Rime of the Modern Mariner (A modern graphic novel version of Coleridge’s famous poem set in an environmental apocalypse, and beautiful to behold.)

- Melissa Miller, Inadvertent Disclosure (A fun, formulaic read about a female lawyer who uncovers a small-town conspiracy to capitalize on the gas boom.)

- Upton Sinclair, Oil! (This was the basis of the film, There Will be Blood. As I read it, I often felt Sinclair was writing about Tioga County in the twenty-first century. Plop an energy boom down in any century and the same shit happens, it seems.)

- Brian Wood, The Massive (A comic book series involving a black ops-soldier-turned-pacifist-leader of an environmental group called Ninth Wave and set in an apocalyptic future. They are aboard the Kapital searching for their sister ship, The Massive. I’m still early to this series, but I’m digging the issues it raises. The colorist, Dave Stewart, has worked on Mike Mignola’s Hellboy.)

Poetry

- Mathew Henderson, The Lease (Fantastic.)

- Ogaga Ifowodo, The Oil Lamp

- Julia Kasdorf’s poetry on the peopile living above the Marcellus shale. (I don’t think she’s published her natural gas poems yet, but they are fantastic for the way they capture the complexities of living above the Marcellus shale. A privilege for me to read.)

- Lisa Wujnovich, Fieldwork

Films

- Gasland (documentary)

- Gasland II (documentary)

- Promised Land (feature)

- Split Estate (documentary)

- Triple Divide (documentary)

Egghead Books

- Kenneth Burke, A Grammar of Motives

- Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives

- Kenneth Burke, Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method

- Sharon Crowley, Toward a Civil Discourse: Rhetoric and Fundamentalism

- Kevin Michael DeLuca, Image Politics: The New Rhetoric of Environmental Activism

- Kim Donehower, Charlotte Hogg, and Eileen E. Schell, Rural Literacies

- David Ehrenfeld, The Arrogance of Humanism (I read this a long time ago, and this book changed everything for me.)

- Terry Gifford, Pastoral

- Don Duggan-Haas, Robert M. Ross, and Warren D. Allmon, The Science Beneath the Surface: A Very Short Guide to the Marcellus Shale (New.)

- Albert O. Hirschman, The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy

- Norman J. Hyne, Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling, and Production (2nd edition) (Great reference book.)

- Jimmie Killingsworth, Appeals in Modern Rhetoric: An Ordinary-Language Approach

- Jimmie Killingsworth and Jacqueline S. Palmer, Ecospeak: Rhetoric and Environmental Politics in America.

- Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Another book that changed everything.)

- Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Idea in America

- Robert W. McChesney, The Problem of the Media: U.S. Communication Politics in the 21st Century

- Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming

- John D. Ramage, Rhetoric: A User’s Guide

- Terre Ryan, This Ecstatic Nation: The American Landscape and the Aesthetics of Patriotism (Super.)

- Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics

A Natural History of Community

July 24, 2013

by Jimmy

The first spring we lived in the Whitney House, I heard a noise in the field to our west that drove me nuts because I couldn’t figure out whether I was hearing a bird or a frog. I only heard the eeent in the evenings, right around the time the peepers cranked up, meaning dusk. I’d listen and listen, trying to make the noise with my nose and mouth and transcribe it in letters. I asked friends who knew more about the local fauna than I did what it might be. Some suggested a type of frog; others shrugged. Even though I looked for it, I never saw what made the noise.

The second spring, nothing.

The third spring, I heard the eeent in a field on the east side of the house. I paid more attention this time around, noting that the eeents started right as the peepers wound down and the birds had settled in the for the evening. Each night I heard eeent, I wrote down the times: 7:15 p.m. 7:37 p.m. 7: 49 p.m. I asked some local friends (again!) if they knew what it was, but no one did. I searched the net and our field guides. No luck.

Then one Sunday night after a couple of beers, I decided I was going to track the source of that eeent, no matter how long it took. I sat on a downed willow branch on the east side of the yard facing the field around 7:50 p.m., listening to the peepers and songbirds settle for the night and watching the trees turn from green to gray. I waited, sure that the maker of the eeents would take the night off, but determined to sit there until complete darkness fell.

Eeent. I looked at my watch. Eeent. 8:03 p.m. . . . Eeent. I stood up and began walking straight toward the sound, trying to make my way as silently as possible through the briars, small trees, and piles of brush that separate our property from the field. Eeent. After walking a log and crawling through some briars, I popped into the edge of the field, just in time to see a bird take off near a rotting stump about 4’ high. A bird! I exulted. At least now I know it’s a bird!

Sure that I had spooked it for the rest of the night, I walked over to where I saw it take flight. Moments later, I heard eeent about 50 yards further up the hill. I looked at the ground where I saw it before, hoping to see something that might help me identify it. Maybe a nest. Anything.

I saw nothing.

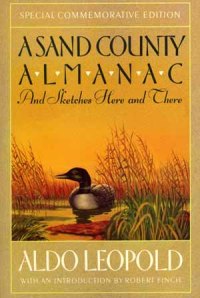

I stood and turned to zero in on the bird’s position when I heard a weird twitter circling the field. I turned again, trying to follow the sound, wondering if it was the same bird. Staring up at the nearly dark sky, I saw a darker shape against the sky flash across my line of sight, like Batman zipping across the Gotham night sky. Then I saw a small bird land fifteen or so feet away. I froze. Eeent. Damn! I thought. I read about these birds in A Sand County Almanac. What did Leopold call them?

“The drama of the sky dance is enacted nightly on hundreds of farms, the owners of which sigh for entertainment, but harbor the illusion that it is to be sought in theaters.”

It was too dark to see the bird well. I noticed it was about the size of my fist, and when it turned away from me, I lost it completely in the not-yet-green grass. Until it launched. I stood there for twenty or thirty minutes, listening to eeents, seeing the launch, and hearing the twittery call circling the field and transforming into the water-trickling-through-rocks sound that preceded the bird tumbling out of the sky. While the bird didn’t land that close again, I began to feel the rhythm of its ritual and got better at predicting where I would see it silhouetted against the sky.

Once I had bothered the bird enough, I walked back to the house and pulled out my copy of A Sand County Almanac. Under Leopold’s section called “Sky Dance,” I read once again about the American woodcock’s mating ritual, the very thing I witnessed. Leopold called the eeent a peent, and he said that, though he enjoyed hunting woodcock, he never shot many because he couldn’t imagine his Wisconsin farm without the sky dance. I picked up a bird book and looked up the American woodcock. It’s a small brown bird with a long bill that relies on camouflage for protection. (One of my students told me that, if you can spot them, it’s possible to gig woodcocks like you would a frog. Camouflage is the bird’s defense. He also says they’re delicious.)

I returned to the field several nights after that to watch the sky dance. Every time I stepped out the back door around dusk, I now heard the twitter that accompanied woodcock’s flight. I noted how the weather affected the dance—clouds meant no dance—and noticed one moon-bright night when Lilace and I returned home after seeing Kris Kristofferson that the woodcock still peented away at 11:00 p.m. This little bird connected me to this place in unexpected ways, snapping me out of my human world and reminding me that creatures live by rhythms and rituals different from my own. My experience watching and listening to this bird has given me a history with this place that I did not have when I moved here. Now, I feel closer to the land, more connected, the same way wading the creek, getting into a yellow-jackets’ nest, catching brown and rainbow trout, and eating turnip greens and shelly beans grown in the garden made me closer to my grandparents’ land in NC. These experiences give me a sense of community, a rich context in which to live my life.

So, how does a place like this become a “zone,” ripe for drilling? One way is when legislation gets written that takes the three-dimensional world we and the woodcock live in and turns it into two dimensions. Such an act of language abstracts a place.

Take Act 13. Act 13 states that unconventional wells must be sited 500’ from houses or water wells, unless given permission otherwise by the land owner, and that well pads must be sited 300’ from residential buildings. Like other bills, Act 13 spends much ink defining terms, stating clearances and environmental expectations, explaining the permitting and other bureaucratic processes, and so on. What the bill does not say is that Jimmy Guignard watched the sky dance of an American woodcock in April 2012, he learned something, and he created a memory which connects him to that place in ways that should be respected. He has a richer history here now.

As measured with my trusty 100’ steel Stanley tape, I watched the woodcock 271’ from my back door. Potentially, that means the woodcock had a whopping 29’ buffer between himself and the edge of a well pad. To the person siting a well in an office down the road, they see numbers enshrined in language that they apply to a map which then becomes a well pad. The dimensions on a page transfer to dimensions on the land. Since I live here, I see wildlife trying to make its way in the world the same way I am and my kids will—as best it knows how. The memories are written into the landscape. Those are two different ways of knowing. The former is abstract—the gas companies can transfer ACT 13 dimensions to any piece of land anywhere. The latter is not—though I may see woodcocks elsewhere, I cannot transfer my experience in the Whitney House to another piece of land as easily. For starters, the mystery won’t be involved.

One could argue that building the pad and drilling is not abstract at all, and they’d be right. I’ve pushed down trees with a bulldozer, and there’s nothing abstract about it. But the issue I’m trying to hone in on has to do with our attitudes before we unload one dozer. Act 13 tells us to look at the land as a zone marked by numbers. It’s abstract and inclines us to focus on only one thing—extracting gas. In contrast, my experience tells the story of me seeing the land and its inhabitants as players alongside my own attempt to create a meaningful life. It’s holistic, one that stresses community.

We all have experiences of places, like my experience in the field next to our house, that give those places meaning to us. And we have all experienced the distress that accompanies something changing a place that holds those meanings for us, especially if whatever is built or drilled shows little or no regard for our history with a place. These feelings run deep. To this day, my aunt in North Carolina refuses to go to a grocery store built ten years ago on the flank of Grandfather Mountain because “they tore up part of the mountain.” Mind you, it’s a small part of a big mountain, but I get where she’s coming from. (They also destroyed a rather poorly-built, but lovely, trail straight up the side of that big mountain.) I’d like to figure out how to inject more awareness into bills like ACT 13 so that they more deeply take into account the places or communities they disrupt.

I don’t expect bills like ACT 13 to include my experiences. That’s impossible. But I do think such bills and the people who enact them need to recognize more carefully that they aren’t working on a blank slate. It’s easy to inflict damage on places we see in the abstract, as containing only one thing we need, like natural gas. Leopold writes, “It is inconceivable to me that an ethical relationship to land can exist without love, respect, and admiration for land. . . . Perhaps the most serious obstacle impeding the evolution of a land ethic is the fact that our educational and economic system is headed away from, rather than toward, an intense consciousness of land.” Act 13’s dimensions encompass all kinds of daily dramas, big and small, but the language flattens out the details of those dramas, the consciousness of them. Though I don’t know how to to do this, we need more bills written with Leopold in mind. He took what was seen as a worthless piece of Wisconsin farm land and made it come to life in deeds and words. He took a zone and made it a community. “As a land-user thinketh,” he wrote, “so is he.” Peent.

Conference Presentation, ASLE 2013: Red, White, and Bluewashing: Visual Rhetoric and Fracking the Marcellus Shale

June 10, 2013

by Jimmy

I recently attended the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment’s Biennial Conference at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. (First conference I’ve travelled to for which I bought carbon offsets.) While there, I gave a version of my research on how the gas industry uses the images of the American flag, the roughneck, and the pastoral to appeal to deeply held cultural beliefs, thus simplifying a complex issue. I call it red, white, and bluewashing, and I wrote an earlier post about it in which I focus on language instead of images. This is the image version, and I’m posting it because an audience member requested I do so. My notes mingle with the images from my PowerPoint slides. Long post, lots of pictures.

Now, imagine you’re sitting in Fraser 119 on the Jayhawk campus. I start to speak. Brilliance ensues:

Have any of you seen Matt Damon’s movie Promised Land? [Few to no hands go up.] It’s about a landsman who goes into a small town much like mine and begins leasing property for future gas drilling. Not a very good movie, I don’t think, but worth watching for the way it portrays how the natural gas industry works to control the message when it comes to gas drilling. I live in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, right above the Marcellus shale. Our county is has the second or third highest number of wells in Pennsylvania, and this presentation focuses partly on how the industry uses certain images to control the message about natural gas. [A woman interrupts to ask where exactly Tioga County is.] That would be helpful to know, wouldn’t it? North-central PA, about fifteen miles south of the New York border. Sorry about that. OK. I want to talk a bit about how the industry works to control the perceptions of natural gas development and the places it occurs, and how this affects people who live above the gas. I’m going to argue that they confuse the issue by oversimplifying it and making it hard to get good information. Today, I’m going to focus on three images the industry uses—the American flag, the roughneck, and the pastoral—to examine how they shape public perceptions of natural gas development.

Images serve as visual terms or shorthand for a set of values that apply now while drawing on key associations or definitions from the past. These are terms that can apply in many contexts, and often seek to promote a particular message. Images often make something complex seem much simpler. The images discussed in this presentation draw on two deeply-held cultural beliefs in America: nature as a resource and nature as something to preserve. In the end, I hope to show how these terms function to create a particular perception of this place, one that is conducive to gas development.

First, let’s talk about patriotism, as represented by the American flag. Here’s is a photo of Shell Appalachia, about a mile from my house. Notice the American flag flying, even though they are based in the Netherlands. In the middle left of the photo’s background you can see a fresh water pit they built and use to store water for fracking.

Patriotism means, well, being patriotic or showing devotion to or belief in one’s country. It’s a complex word used in a number of contexts, depending on what we need. It’s hard to criticize “patriots.” Companies flying the American flag may be sincere in their beliefs, but the flag also acts as a shield to blunt questions or ciritcism. We don’t question patriots, especially in time of crises. Here’s a billboard from Chesapeake. Notice the flag prominently displayed in front of the drill rig.

Flags represent nations, not places. In other words, they serve an abstracting function. I don’t fly the Guignard flag in my yard, or the Whitneyville [my town] flag, or the Tioga County flag. I fly the American flag. It marks me as a part of something larger, someone devoted to the idea of a nation. Patriots make sacrifices—think soldiers going to war. Think American citizens during WWI and WWII. Terry Engelder of Penn State has called this place a “sacrifice zone.” Engelder sees this as a “duty.” Quite honestly, Engelder’s statement pisses me off, but I haven’t seen him to tell him that yet. [Yes, I said “pisses” during my presentation. It’s accurate.]

On to the roughneck. “Roughneck” is the term used to describe people who work in oil and gas fields. This guy appears on the Marcellus Shale Coalition’s website. He’s a big, burly guy with an upturned collar, hardhat low over his eyes, and serious expression on his face. He’s clean compared to many photos of roughnecks you see. Roughnecks are associated with hard physical work that is often dangerous. The image appeals to the strand of rugged individualism that runs through our culture, and taps into our belief in personal freedom, physical toughness, self-reliance, minimal government, and free competition. Upton Sinclair’s Oil! portrays the idea of the roughneck well.

The image of the roughneck draws on the Turner thesis, the idea that the taming of the American west created a new kind of American identity. The image of the roughneck is a masculine one, representing a man’s world that draws on our cultural strands like taming the frontier, cowboys, and the Wild West. The roughneck above reminds me a lot of this guy.

The image of the roughneck draws on the cultural belief that masculine work counters the “feminization” of men that many of our leaders, like Teddy Roosevelt, associated with cities and desk jobs. Our modern rugged individualists ride Harleys, climb big mountains, and make it big in business, among other things.

Now, the frontier is buried over a mile underground.

Let’s move to the pastoral. The pastoral is associated with farming, rural life, simplicity, peacefulness, and hard but satisfying physical work. The pastoral evokes longing for a simpler life in the garden. Yes, Eden matters here. The pastoral can be represented by this farm, located in the Morris Township in Tioga County. Notice the corn and soybeans between the camera and the barn.

Tioga County is a pastoral landscape, that is, a middle landscape, caught somewhere between civilization and wilderness. Not New York city, Philadelphia, or Pittsburgh, but not the Rockies, the Tetons, or the Sierra Nevada either. And while many people from urban areas may romanticize the place, seeing it a kind of “escape” from the city and work, those actually working the land know that it can be hard to live here, involving long hours, hard work, and little pay.

In the next slide, we introduce what Leo Marx calls “the machine in the garden.” That is, we introduce technology in the form of a drill rig, trucks, storage tanks, etc., into a landscape previously seen as simple and peaceful.

It’s worth noting that the industry often frames these rigs with forest or farms to draw on our pastoral impulses while also appealing to our deep-seated desires to use such resources. Things appear harmonious. The press presents similar images, which draw on similar framing but sometimes suggest that the process is not as clean as we might think. Here are examples from the New York Times and Propublica.

The two photos suggest that the drilling process might not be as clean as we hope it is. However, I would argue all three images of the drill rigs contribute to what I would call an “industrial pastoral” or a pastoral landscape in which the rural and technology come together in seemingly benign ways. Such images help us reconcile the contrary impulses of preserving nature and using it. Couple this with the idea of the roughnecks working on the rigs—good, masculine work—and we begin to see how such images serve to present a particular view of the industry that ties into deeply held cultural beliefs.

Taken collectively, the images of the American flag, the roughneck, and the pastoral work by drawing on cultural beliefs, embedded in the American psyche in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, of using nature and preserving it. The three recurring images draw power from each other, reinforce each other, and derive meaning from each other. These images serve an abstracting function, that is, they tap into cultural beliefs from long ago that still resonate deeply with us and serve to transform a community into a zone that needs taming, similar to the way we saw the west during Manifest Destiny or the desert southwest during the nuclear tests of the 50s (for which the government defined people living there as a “low-use segment of the population”). Once a place is abstracted, it’s easier to industrialize it. The industry recognizes this.

We are more willing to develop a place, perhaps even destroy it, if we see it as a blank space on a map.

Drilling for natural gas a complex process that calls for nuanced conversation about multiple concerns—social, cultural, political, economic, and environmental. By drawing on images like the American flag, the roughneck, and the pastoral, the natural gas industry makes it more difficult for the public to understand fully the stakes of drilling for natural gas. Further, the industry’s use of these images works to persuade people not from this region to view gas development favorably because the images tap into national narratives rather than telling the stories of the people who live in this place. The way we view places is the way we use places. Thank you.

I cut two images from the New York Times and the Wellsboro Gazette, because I don’t have digital copies of them. The NYT ad portrays natural gas in the abstract, while the WG ad, bought by Chesapeake Energy and is titled “This Is Our Home,” suggests that the gas industry has close ties to this place.

Two books super important to this research: Terre Ryan’s This Ecstatic Nation: The American Landscape and the Aesthetics of Patriotism and Kevin DeLuca’s Image Politics: The New Rhetoric of Environmental Activism.

Thanks to all who attended, asked questions, or made comments (especially the woman who talked about religious imagery in the NYT ad that you can’t see) and to my co-panelists Jimmie Killingsworth (Texas A&M and the dude who envisioned the panel) and Diana Ashe (University of North Carolina, Wilmington). I learned a lot.